The Lean and Just-in-time (JIT) production concept was initially introduced in the industry by Toyota. A big factory needs raw materials to operate. Usually, factories order wholesale amounts of supply to enjoy wholesale discounts, and then they store the raw materials before they are uses, and the next batch is required. It was status quo in all industrial facilities until Toyota decided to look closely at the situation and asked some inconvenient questions.

The raw material storage is not for free. First, you need space to store, and it means you will need more significant facilities than you potentially need for production. Second, raw materials can expire or go wrong, so you need a particular tracking system, and you also need to adjust output to use materials before they expire. Doing this, you might not produce what your customers need right away. So, you will need storage space for the final products as well. Third, moving the materials is also labor, so you need to pay more for the workers who will do it. Forth, the supplier could provide you the wholesale batch size, which does not fit your needs (imagine that the factory produces 3-legged chairs, and the supplier offers only 4-leg packages). Finally, when buying excess, you freeze your money, while the business can use it for something else meanwhile.

So, Toyota decided to calculate if its suppliers’ wholesale discount is worth the additional cost. Unsurprisingly, it turned out that it does not worth it. And Toyota started its long journey to rebuild the supply chain. It came to its suppliers, and said, instead of 2000 suppliers, we will work only with 20, but you will supply under our conditions. The conditions are you will provide the raw materials with the quality we’ll set, the quantity we order and just in time (not before, not after), in return, you can set up the fair price and get life-long contracts… These negotiations made industrial history, and the arrangements are still in place for Toyota.

Though this might be an exciting story for outlook, what does it have in common with household and personal finances?

Often, we act as old-fashioned factories trying to make stocks of raw materials. Think about the following situations:

- Stocking up in wholesale clubs.

- Buying something we do not immediately need just because it’s on sale.

- Buying too many groceries.

- Hold on to things we do not use because we “might need them one day.”

- Dealing with food in fridge or pantry about to expire inventing some creative recopies we do not want.

- Building the whole new system of tracking leftovers: meticulous daily meal planning, pantry tracking applications.

As the old-fashioned factories, we are so sure that it is wise and frugal that we don’t question such behavior a second time. And these beliefs are so engraved into our behavior that it is hard to imagine that you come to the nearby store and don’t see a discount. That is how BOGO deals became the holy grail of commerce.

But do we benefit from such behavior? We threw away expired grocery: an average American family wastes 250 pounds of grocery per year. We need bigger and bigger closets for our wardrobes: the average American woman has 103 items in her wardrobe, 20% of the clothes are unwearable, 12% of the wardrobe still has tags on it. We are moving to bigger and bigger houses, while the self-storage industry size is almost $40 billion annually (for comparison, car production industry size is $80 billion). Those are real numbers, but you also can think about the time and emotions you spend managing, cleaning, arranging your closet, stock, pantry, fridge, and other stuff. Isn’t it too high price already?

So, how can we learn from Toyota to optimize our life? While Toyota had its suppliers to negotiate, we must deal with ourselves as it comes to housekeeping and personal finances. The changes we need to implement are behavioral, thus the hardest. Below there is advice based on my personal experience.

“What if I need it one day”

I grew up in the USSR, where everything was “deficit,” meaning you cannot simply go to a store and buy something. People had to “get” things through connections and references. And there is a very probable possibility that you might need something later. My family stored almost everything (and to be fair, many things found useful with some time). The time has passed long ago, but I still catch myself wishing to keep something for the same reason.

Common sense tells us if we have not used a thing within a year, we can probably live without it. And it is better to let it go. However, there is a significant probability that you will “need” the thing as soon as you let it go in real life. It is a trick your brain plays with you: it subconsciously brings up a subject from recent emotional experience (letting go is the emotional experience for many of us).

I learned how to beat my brain in its game: before letting go of a thing, I set the plan. 1. If I need to repurchase it, where can I do it, and how much it costs? 2. Is there something in my possession I can immediately replace it with? After I have a plan, I let the thing go.

The first question removes the subconscious anxiety that I give away too valuable thing, and I will not be able ever to replace it. Usually, quick research on Amazon, eBay, Etsy, etc., shows that the item is not so rare or valuable as I imagine.

The second question lets secure the positive effect of allowing to go in the future. Here is how it works:

Too much food

Overbuying the grocery is a common problem. I hate to throw it away; I treat each time as my personal failure. It is a mixed feeling of pity for thrown away money and embarrassment of being a not good housekeeper.

Now I have strict rules on how I do grocery shopping. Here they are:

- No hungry shopping. Everybody tends to buy much more when hungry. So I made it a hard rule: eat before going to the grocery store.

- Shop for three days. I used to shop once a week for the whole week, and I always (always!) ended up with food leftovers. So, I decided to try to shop for three days ahead instead. Guess what? I still go shopping once per week and have almost no leftovers!

- Meal plan. The same as my 3-days grocery horizon, I do meal planning for three days. And my meal plan is a list of 3-5 dishes I could cook within the next three days. The three days are magically turning into the whole week because of leftovers and occasional dining out.

- Shop in the pantry/fridge first. When I plan meals, I see what I still have in my storage areas and supplement my grocery list only with missing ingredients. It helps to rotate the things there and decreases my weekly grocery check.

- Shopping list. I know that I will buy what I do not need without the list and will not buy what is required.

I also set a mental “plan” to lower my anxiety about the situation when I ran off food. The following thoughts made me very calm: 1. People do not die if they miss one or two meals. It is even good for your health to do intermittent fasting. 2. I have a stock of long-lasting “Emergency food” planned for unexpected guests. My family does not eat such food daily, but if my friends, my mother-in-law, or my daughter’s friends, or whoever else comes, it is there. 3. I set an “Emergency shopping” plan: where I would go if I urgently needed food (I am lucky as I live 5 minutes away 24-hours pharmacy).

I have never executed my plan, but having it is imperative.

Smart with wholesale clubs

You cannot negotiate with wholesale clubs. You either use them or not.

It is undoubtful that it is much cheaper to buy goods there. But is it really for you? In my situation, I live in a small apartment, so the room for physical storage is limited.

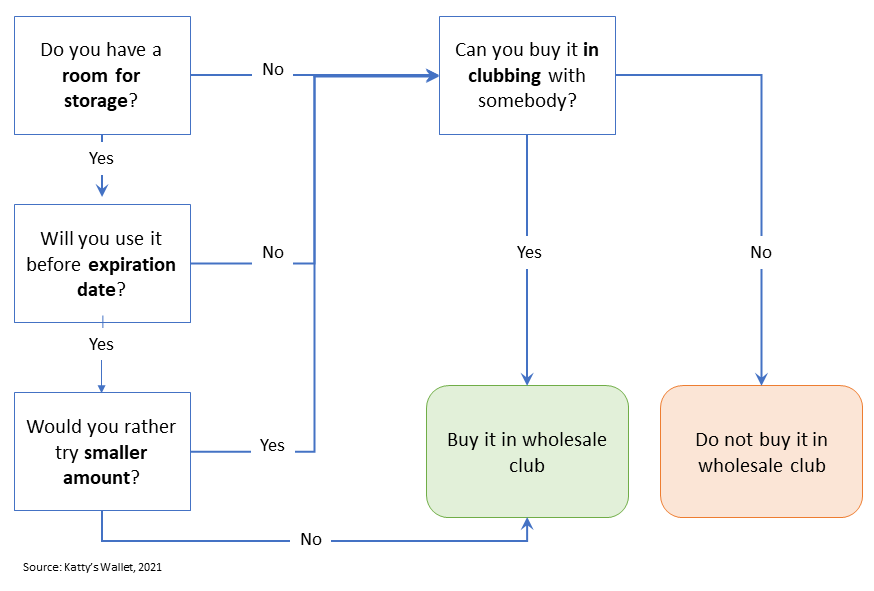

Here is how I approach the question:

- Assess the room is needed for storage. When will you store it?

- What is the expiration date, and what is your typical consumption of the thing.

- Is there a possibility to buy the things in clubbing together with family, friends, or neighbors?

- Would you rather have a smaller amount to “try”?

I shop in wholesale clubs with this approach in mind, but I do not buy everything there.

Discount as purchase trigger

People love sales. I am with you; I really am. Moreover, I use deals very effectively for expensive things. For example, I never buy designer clothes at the full price. Please do not treat me wrong, I can afford them, but I never do. The reason is I know that it is a 90% chance that the thing I like will eventually go on sale (10% is left for the super-rare case when the item is so popular that it is gone long before the sale time – well, I can live with that).

But there is another aspect of the sale: when the retail industry uses sales to make us buy something. They are damn effective; they trigger the feeling of scarcity (notice that each sale always has “only by…” field) and accumulation instinct. Even if you do not need the things, your brain immediately switches from rational mode to reflex mode, “get it and run.” And later, we look at unmatching clothes from “final sale” or at literally the 10th toothpaste in the stockpile and feel regret.

That is incredibly hard to resist. The reason for that is that though the brain switches immediately from rational to reflex response, it is not trained to switch back fast enough. By the time it starts reasoning, you have already purchased something and sitting home regretting it.

There are three technics I found helpful:

- I do not buy anything that is not on my shopping list from the small, replenished stuff. If the thing is on sale, then I am lucky. If it is not on sale, I can afford the total price anyway.

- If I see something big on sale, I do not buy it immediately. I put it in my wish list for at least a day (usually, things live there for a month, but sales are time-framed, so I do not want to be unrealistic). If I still like it in a day, well, maybe it is worth it. (If it is already gone – well, at least I save my money.)

- There is an extreme technic of “Zero purchase” store walking. It trains you to “switch brain” without automatic actions. From time to time, I walk into my favorite store (for me, it’s Home Goods), walk around, and buy absolutely nothing. Gosh, it is hard! But each time, I am so proud of myself! And each subsequent time, it is easier. (But if I see I love, I get to the point 2 – and can get back the next day 😉)

–

Wouldn’t it be good if our storages looked like Toyota plants: very clean, very effective, and containing only the things we need? What if your fridge or your pantry would be an example of a lean approach? What if there is no food waste ever?

Toyota has not come to the lean and JIT implementation over one night. It took years and involved a lot of rethinking of default behavior. You also can benefit from this approach. I shared with you my tips, but you can work on your situation and invent your non-common techniques.